It Runs Hot .. Keep the Most Powerful Vehicles Running Cool!

Over the years, I’ve discussed this topic more often than any other with hot-rodders. I’ve proclaimed on multiple times in my books that the electrical system was the foundation for a properly functioning cooling system, etc. Fast forward to 2023 and I’m unable to point enthusiasts to a single source, written by a knowledgeable individual, which ecompasses the whole enchilada. So, here goes. But, be forewarned – many of you won’t like much of what you’ll read here as it goes against conventional wisdom.

Hot-Rodding

I define hot-rodding as the desire to improve the performance of a vehicle beyond what it was capable of when new. In most cases, that also involves increasing its horsepower. There are any number of ways to improve the horsepower of an engine, but for a true hot-rodder that means increasing its efficiency. By definition, a more efficient engine will make greater power from the same volume of fuel. In addition, even greater power can be made from a greater volume of fuel.

Did you ever buy a performance add-on that promised both a power increase as well as better miles per gallon? How in the heck is that possible? Simple – said product improves the efficiency of the engine thereby providing greater horsepower when the throttle is wide open and better fuel economy in part-throttle conditions. That wasn’t a coincidence!

Naturally Aspirated

Enthusiasts that play here simply must be at the top of their game to be competitive as they have no power adders to call into action. The name of the game is to improve airflow and the degree to which that skill is mastered by this group amazes me. No, this doesn’t mean that every car you see at a car show with a single plane manifold and a 750 double pumper is optimized to the nth degree, but when you see such a vehicle with a portable weather station kickin’ in the backseat rolling on drag radials with rubber on the quarters, you may want to think twice about lining up next to it.

Power Adders

Nitrous oxide, blowers / superchargers, turbochargers . . . they all do the same thing – provide more oxygen, allowing a greater volume of fuel to be burned. Each has its pluses and minuses but the level of understanding to maximize a given power adder is about the same.

The Blue ’72 Olds above has a naturally aspirated Olds’ 455ci that makes north of 500hp on pump gas. The Red ’71 Olds is a roots blown 509ci BBC that makes right at 1,000hp, also on pump gas. Both are fuel injected. These are true street / strip cars that rack up lots of miles on the street and never overheat.

Additional Heat

No matter the camp you fall into, It should be obvious that there is additional heat created in the combustion process when burning a greater volume of fuel. However, not one single hot-rodder has ever said to me, “It overheats while it climbs from 3,500 RPM to 7,500 RPM with my foot to the floor.” Never. Not once. It’s always just the opposite – It runs hot while I drive around town. Ah. So, you’ve built a race car and want it to run cool when running honey-dos in 90 degree weather. So, let’s be honest with one another. Which is it – strip or street / strip?

Strip would be vehicles which are designed for the throttle to be operated in an ON/OFF fashion whereas street / strip would be those built to run around on the street which can also tear it up on the strip on a Friday night. Want your race car to run cool on the street? Run methanol . . . and some do.

For the rest of us, this means we’ll need to understand and focus on the following:

- Cooling system – this includes a water pump capable of moving the correct volume of coolant, correct thermostat for the application, fans capable of moving the correct volume of air, a correctly designed and implemented fan shroud, and a correctly sized radiator*

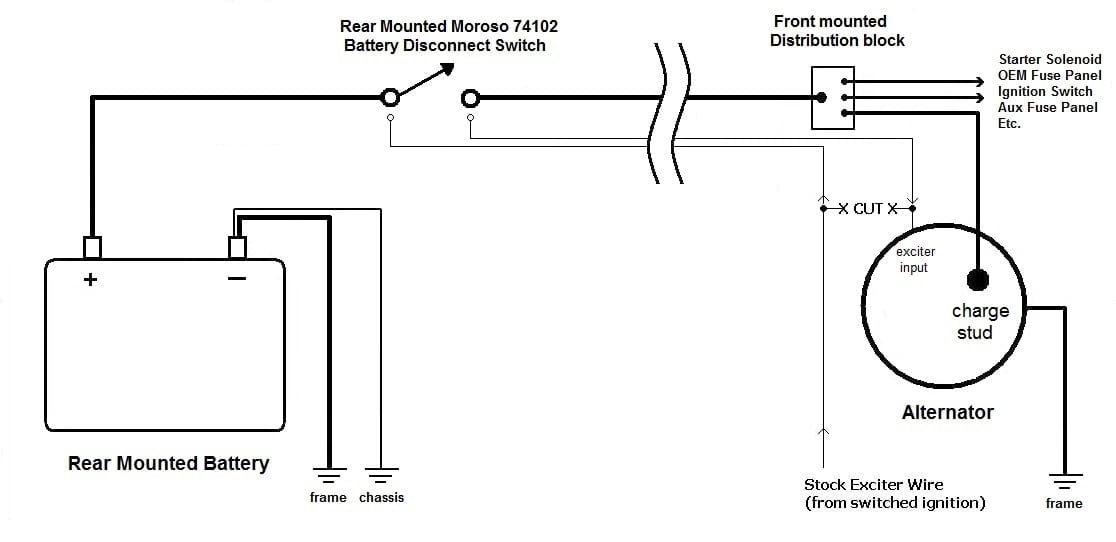

- Electrical – this includes a correctly sized alternator driven at the correct drive ratio and minimal voltage drop to the cooling fan(s) themselves, our specialty

- Engine tuning – the engine should be properly tuned for efficiency

*We defer to the experts at Ron Davis Racing Products in Glendale, AZ for such support and have since 2006. Nobody knows it better.

We’ve got a LOT of ground to cover. However, the juice will be worth the squeeze as you’ll be able to cruise your hot rod all day long anywhere without risk of it overheating if you embrace it all. So, let’s get started.

Electrical

As I’ve said many times before, the electrical system is the foundation from which all other vehicle systems work. Therefore, it’s our starting point. [We’ve built a business around it and you’ve found us – thank you!]

Charging System

I’ve addressed all the basics extensively in three other blogs. Here they are, and each is required reading.

Charging Systems 101

High Output Alternators 101

Getting Grounded

If you’re looking for additional reading material on the above, including installation and application specifics you’ll find it in my books.

Minimizing Losses

Cutting right to the chase, all cooling systems which employ electric fans require plenty of Power be available to the fans. Power is the product of Voltage and Current and is a measure of work being done. Electric fans respond to Power, not just Voltage. More Voltage available equals more Current delivered. Voltage drop is what we want to avoid as that limits Current – we minimize it with correctly sized quality parts which have been assembled correctly.

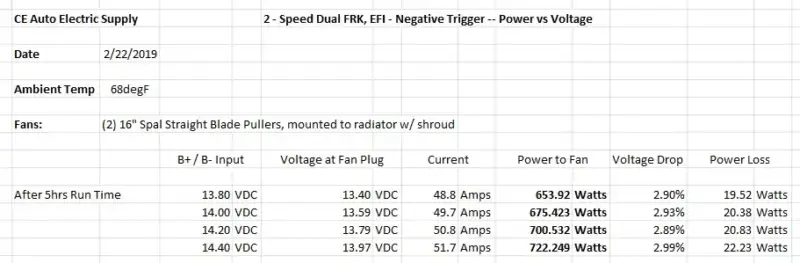

Consider the above Power vs Voltage analysis we did on our 2-Speed Dual Fan Relay Kit with a pair of 16″ Spal straight blade puller fans. Notice the difference in current delivered to the fans as voltage increases and the net effect that has on power delivered to the fans. Compare the power at 13.8V to the power at 14.4V for an idea of just how much work is lost at the lower voltage – 9% to be precise, and that’s a bunch. In a vehicle, heat is an indicator of work being lost. In our business, we look to minimize losses at every turn – it drives our product development.

The typical fan relay kit is a compromise from the word go. Cheap relays, cheap fuse holders and fuses, cheap thin-wall brass terminals, and 12 AWG wire max. Performance was never a design consideration as it drives the cost up significantly. We do just the opposite – we buy the best relays we can buy, use only OEM grade tin-plated heavy wall terminals, integrate the fusing into the module itself, use 10 AWG cross-link wire, and crimp and solder all such terminations. The performance difference is not insignificant. Instead of wasting power as heat, we put that power to use to spin the fans. While our Fan Relay Kits are not inexpensive, you absolutely do get what you pay for here.

Engine Tuning

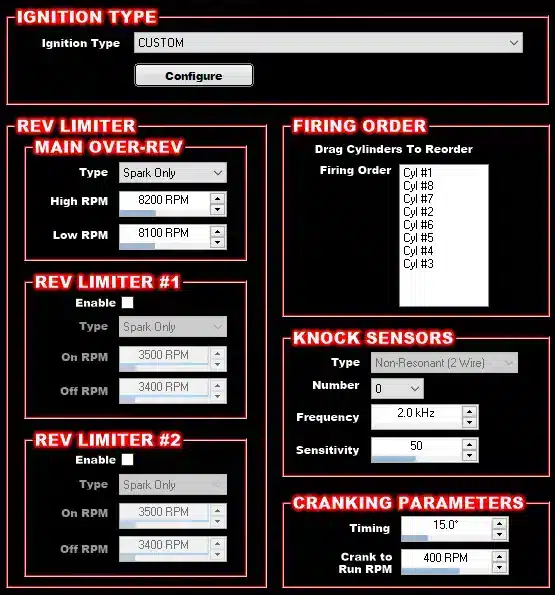

For the drag strip, it’s not at all desirable to have a timing curve. Rather, all forms of advance (mechanical, vacuum) are eliminated and the distributor locked out at the desired timing for wide open throttle. In a carbureted application, a timing retard module is traditionally used to retard timing significantly to be able to start such an engine. For an EFI engine, you simply populate a cell with the desired timing at start-up (below right).

As the throttle is used in an ON/OFF application, there is no curve so to speak. When the throttle is opened fully, we want the engine to have the timing required to fully burn the mixture. Tuning is accomplished by reading the plugs and modifying fuel metering and timing accordingly.

None of this is desirable for a street / strip application. If this describes your present situation, it’s a major contributing factor for your engine running hot. Absolutely no locked out distributors allowed!**

For street / strip or even just plain street, we need to utilize advance, and a lot of it, to burn the mixture fully in part throttle conditions. Unburnt fuel in the exhaust creates heat! The more fully the mixture can be burned, the lower the exhaust gas temperature (EGT) will be.

The procedure differs from carbureted to EFI, so each is addressed individually below. The art of designing an ignition curve for a given engine is just that, an art. It’s a function of RPM, MAP (Manifold Absolute Pressure), and AFR (Air / Fuel Ratio) and it will be different for every engine. Generally speaking:

- Timing is a function of initial plus advance. A timing curve determines the rate at which the timing comes in, how much total advance, and when.

- The exact timing required at a given RPM at a given load is a function of the target air / fuel ratio at that same point.

- A leaner mixture (higher AFR) requires more timing (or lead) to burn fully while a richer mixture (lower AFR) requires less timing to burn fully. [Read that again if need be.]

As each of the above pertains to tuning, there are four areas that should work harmoniously together – idle, transition from idle, drivability, and wide open throttle. All wide open throttle tuning need be done in a controlled setting by a competent tuner so that the engine isn’t damaged.*** That can be an engine dyno, chassis dyno, or even a dragstrip (as outlined above).

A properly tuned engine with the correct amount of advance in the idle and drivabilility area will have better fuel economy, create less heat in the combustion process, have less unburnt fuel in the exhaust, and as a result make less noise as compared to an improperly tuned engine. Less noise isn’t a bad thing here, but it can be counterintuitive. Less unburnt fuel in the exhaust means less heat that the coolant has to wick from the cylinder head. Hey, now we’re getting somewhere!

But how much is just right? It’s been my personal experience that even the most powerful street / strip engines can require as much as 45-50 degrees of advance to burn the mixture fully in the drivability area. [Late model engine platforms may differ.] Some engines like even more. While this differs from conventional wisdom, it’s quite accurate. So, how do you accomplish this?

Carbureted Applications

You’ll need more advance than the centrifugal advance alone can provide. One solution is vacuum advance. Vacuum advance on a hot-rod? Yep. Of course, utilizing this does require a camshaft that makes enough vacuum at idle. If your camshaft makes enough vacuum at idle, you’ll be running a distributor with both centrifugal and vacuum advance. If your camshaft doesn’t, then an ignition system like the MSD Programmable 6AL-2 or their Power Grid will get you there. If you do have to run a box like that, then you will in fact have to lock out all forms of advance in the distributor and program your timing curve in the box itself via a laptop.

Vacuum advance offers the best of both worlds as the advance is reduced as load (MAP) increases. So, let’s say that your engine tuner determined that your engine made peak power with 35 degrees of timing. In addition, you’re using a vacuum advance canister good for a maximum of 10 degrees of advance. Finally, your combination requires 45 degrees of lead from 2,500 – 3,500 RPM at 10 inches of mainfold vacuum at 14.7:1 AFR to burn the mixture fully while cruising at 55 mph on level ground (minimal load on the engine, so manifold vacuum is at its highest). This means that your centrifugal advance would have to be all in by 2,500 RPM to achieve that timing goal.

As you go up a hill, load is placed on the engine and manifold vacuum decreases, reducing the amount of total advance and keeping the engine safe from pinging. When you whack the throttle wide open, the vacuum advance is eliminated and you’re right back at the 35 degrees your tuner determined was what the engine wanted to make max power and do so safely. Wide open throttle performance will actually increase due to the fact that you’re burning the mixture more fully when you’re cruising around vs sooting up the plugs . . .

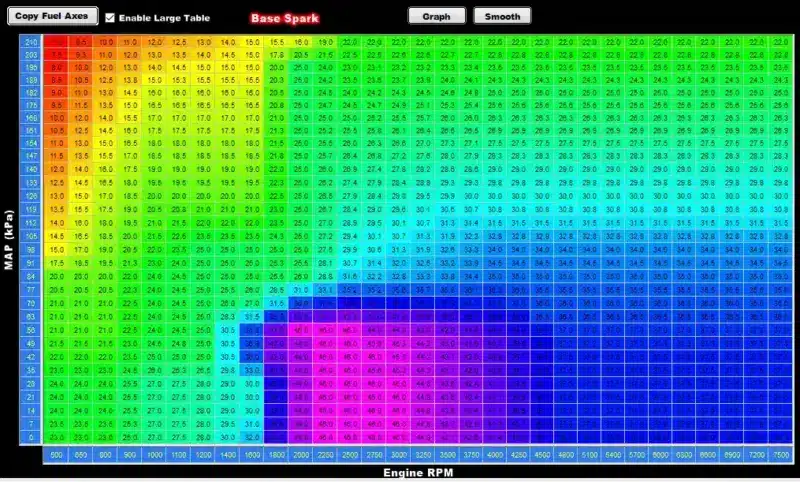

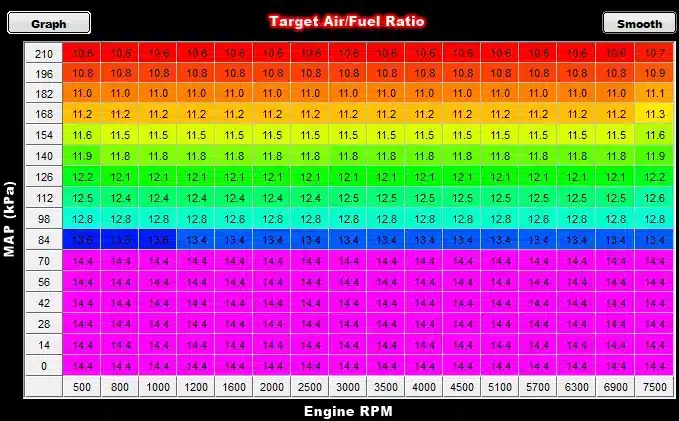

EFI Applications

We don’t think in terms of initial plus advance here. Rather, we build the timing curve in the ECU – MAP on the vertical axis and RPM on the horizontal axis. This overlays exactly on the Target AFR map and each is dependent of the other. Same net result, simply a different way to achieve it. [Incidentally, this should provide some insight into the relationship between ignition timing and AFR.]

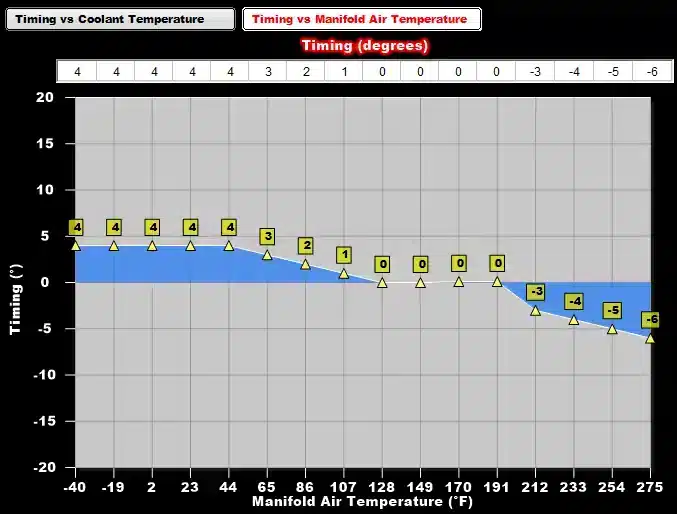

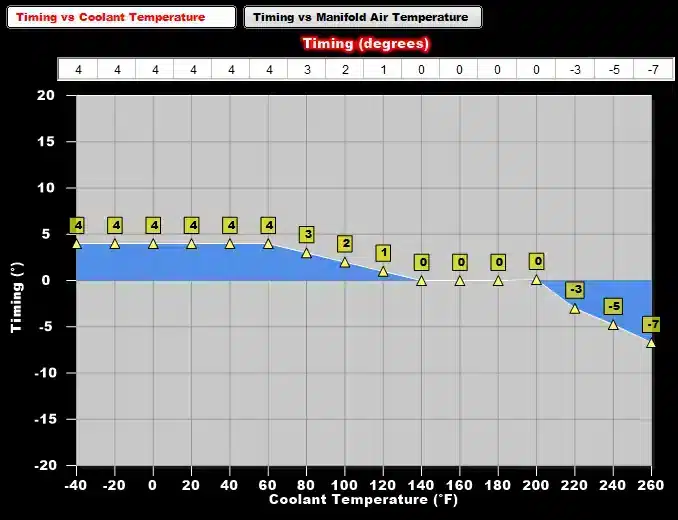

Advanced systems allow you to implement timing modifiers to alter timing based on:

- Intake Air Temperature (IAT) – as IAT increases, timing can be retarded

- Coolant Temperature (CTS) – as CTS increases, timing can be retarded

That way your engine always has a safe tune, no matter the conditions. As there are college level courses taught on the topic of tuning, that’s well outside the scope of this discussion. I’m not a tuner myself, but I have done my own drivability tuning for years now. It’s really not that difficult but it does take some tools to do so correctly. Bare minimum would be an AFR meter and a nice, large vacuum gauge.

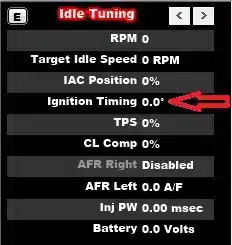

The Holley software (of which all of the above screenshots are from) provides a small window at the bottom left which shows you the actual timing in the engine in real time, which reflects all modifiers. The same can be said for net AFR. Both are excellent tuning tools. [Engine is not running here . . . ]

Generally Speaking – Carbureted or EFI

Tuning for maximum efficiency isn’t accomplished in an afternoon and you’re done. Rather, extensive driving sessions are required to put the engine into load in all different possible scenarios and seeing how it behaves as a result. Too much timing can cause the engine to “buck” a bit on level ground with high manifold vacuum. In addition, too much timing can cause detonation (ping) as it’s loaded, even slightly. Reducing timing in the offending areas is vital.

Some tuners use Mustang dynamometers to do said drivability tuning in a controlled setting. Such a dyno allows the tuner to load the engine similarly to driving the vehicle on the road. Competent tuners are not inexpensive so many convince themselves that they can’t afford their services. What’s less expensive – a dyno day or a damaged engine?

***Tuning by committee or in internet discussion groups often results in very expensive engine parts scattered on the ground . . .

Naturally Aspirated vs Power Adders

By now, it should be obvious that advance is your friend as it pertains to reducing operating temperature in the idle and drivability areas – the two areas that street/strip vehicles need the most help. What if you have a big ol’ 8-71 blower? How about a pair of turbochargers? Surely, you don’t want that much timing then. You do actually, but it needs to be managed differently. Street / strip engines with blowers or turbochargers have similar street manners as naturally aspirated engines until they’re in the boost – which is a very small percentage of time.

If I take my roots blown ’71 Olds’ out for the evening and drive it 2 hours, I may only be in the boost for a total of 30 seconds the whole evening. The other 1 hr, 59min, and 30seconds it’s just a 9.5:1 compression engine with a large, shiny, cool looking, awesome sounding parasitic draw sucking horsepower from the crankshaft when it isn’t making boost. Correctly tuned, this combination has excellent drivability, doesn’t overheat, and doesn’t sacrifice wide open throttle power – it’s available instantaneously. You really can have it all.

So, everything outlined above applies here as well. What’s different is managing timing when under boost – also well outside of the scope of this discussion.

Here’s a video of the Olds out and about with all of the above employed. 75deg evening, after driving it for 30-45min. Notice RPM, coolant temp, manifold vacuum, air/fuel ratio, and how snappy that throttle response is!

Pitfalls to Avoid

Tuning an Engine which Requires Repairs

As tuning is such a methodical and sometimes lengthy process, you want to start with an engine that doesn’t require repair. The engine should start easy, idle smoothly, and run well down the road before you start to improve things. With EFI Conversions (hey, that would make a great book title!) being so popular, it’s SO easy to overlook the basics.

Oil consumption contaminates the exhaust. This is interpreted by oxygen sensors as leaner. If you’re tuning with a wideband O2 meter, you’ll get bad data. If you’re tuning via the ECU’s O2 sensor, this is interpreted as leaner than target which in turn directs the ECU to richen the mixture. [This is one of the things that pushed me over the edge on a new engine for my Olds’. As time went on, the amount of oil in the exhaust affected the idle and drivability tuning to the point that there were certain things I just had to live with – some of which affected safety. Want to turn left across traffic? Good luck – the throttle had two positions, ON or OFF.]

Coolant in the exhaust is equally as troublesome as that will ruin oxygen sensors in very short order. Vacuum leaks – impossible to tune an engine with un-metered air entering it.

Iron out all of these problems before beginning any tuning effort. The point is, you sure don’t want to spend a bunch of time tuning an engine that isn’t ready to be tuned – or your tools may end up on the lawn.

Ported vs Manifold**

Which do you use? The correct answer is manifold. The difference is that manifold vacuum is present even with the throttle blades closed whereas ported vacuum is available only with the throttle blades open. The exception to that rule would be in a carbureted application where the camshaft simply cannot make enough vacuum at idle to fully activate the vacuum canister which can cause a rough idle. Moving the vacuum source to ported would alleviate such a rough idle condition while still providing the advance in the drivability area. Certainly not ideal as the mixture won’t be burned nearly as fully at idle, but a compromise worth making.

The additional timing is desirable feature when not running fat at idle, which most hot rods do. Admittedly, that does sound pretty damn cool. However, in addition to sounding cool, it can also foul the plugs in a hurry.

It Runs Better without the Vacuum Advance

If you disable the vacuum advance and your vehicle idles better or runs better in the drivability area, then this tells you that something isn’t quite right. The first thing to consider is point 3 above – A leaner mixture (higher AFR) requires more timing (or lead) to burn fully while a richer mixture (lower AFR) requires less timing to burn fully. Look at it in reverse. If it runs better without the advance, the mixture may be too rich.

Summary

If you got this far without kicking the dog or sending me a scathing email, then I assume your interest in getting your vehicle running cool is as sincere as our interest is in helping you to do so.

**These topics should never be discussed over Thanksgiving dinner, as fist fights have been known to break out over them . . .